Gameplay Ability System (GAS) in UE5

At the start of this year, I spent several months studying the Gameplay Ability System (GAS) in UE5. I wanted to evaluate its usefulness for both singleplayer and mutliplayer applications, with my logic being that if you are interested in creating both singleplayer and multiplayer games, you might as well learn GAS from the start. As it stands today, I feel that GAS is emblematic of a larger design philosophy that seems to be shared by many portions of the Unreal Engine codebase- one that I am feeling increasingly resistant to.

NOTE: This post is a fairly high level look at GAS. If you are looking for more in-depth information, I suggest looking first (briefly) at the offical UE GAS Overview, then at Tranek's excellent GAS Documentaiton, and finally at the Lyra sample game's source code.

What is GAS

The Gameplay Ability System (GAS) is an official Unreal Engine plugin developed by Epic Games. It provides a system for computing complex interactions between actors. It lets you define special triggers called Abilities that an actor can use to apply some behavior or sequence of behaviors, called Effects.

Main Benefits of GAS

Let’s take a quick look at what the benefits of GAS are.

Interaction

GAS lets you generically define interactions between two Actors. A simple example might be that you can create a “fire” effect that does X points of damage to any actor with a “health” attribute and a “flammable” tag. You can then write some hit detection code for your fireball actor and tell it to apply the effect to any actor it touches. Then, GAS will just automatically apply the effect to the applicable actors.

Common Ability/Effect Behavior

GAS provides some nice built-in behavior that you maybe would need to create anyway. Some examples include:

- Ability Checks: A system for determining if an actor is allowed to activate a particular ability.

- Effect Durations: Want an effect to trigger every 5 seconds for the next 2 minutes? GAS has this built in.

- Effect Stacking: A way to define what happens if an effect is applied multiple times to a particular target.

- Ability Cancelation: A way to handle what happens if an ability is canceled while it is the middle of being executed.

- Callbacks: All the various delegates you would expect for when something in the system changes.

Networking

This is the big one. The Gameplay Ability System comes with built-in client side prediction, meaning that a client can perform some action and see the effects on screen immediately. Then, behind the scenes, the server will validate what happened and respond back with the canonical record of the event. If what the client predicted would happen matches what the server said actually happened, nothing special happens. If the server decided something else happened instead, GAS will automatically roll back the changes predicted on the client side. This helps reduce input latency on the client side and can also help stop certain types of cheating, since the server is the final authority on the game state.

Reality Check

This all sounds great, why would you not want to use all this?

As with many of the things made by Epic, GAS is very much a piece of generalist software: it tries to support any possible use-case you can think of. The thing is though, your game is not necessarily going to need all these features. The extremely wide feature set comes at pretty serious cost: complexity.

GAS is well known for its set-up difficulty: it requires a lot of boilerplate code to be in place order to use it. Set up is frustrating enough that there is even a paid plugin that someone made called Gas Companion that exists just to help integrating GAS into your project.

GAS is an extremely convoluted codebase, often providing multiple ways to do the same thing with slight variation. Want to just apply an effect that does some type of math operation on an attribute? Well, you can use a default Modifier, a Modifier with a custom Modifier Magnitude Calculation, or a Gameplay Effect Execution Calculation. Want to trigger an ability? You can activate the ability by handle, by input action, by gameplay tag, by class, or by event [see tranek 4.6.4]. Each of these has different pros/cons based on what you are trying to do. There are many more instances like this, where you must perform a lot of extra research just to make sure you are actually using the system correctly.

Despite all this flexibility, GAS still forces you into design decisions as well. For example, do you want your damage buffs to be computed off the base damage value of your character (i.e. if your base damage is 100 and you have two 50% damage buffs, your final damage would be 100+(100*.50)+(100*.50)=200), or do you want them to be cumulative (i.e. 100 * 1.50 * 1.50 = 225)? GAS just decides for you that it should be the former, and you actually have to modify the engine code if you want it to work differently [see tranek 4.5.4.1].

Also notice, I’m not linking to the official GAS documentation. This is because like many features provided by Epic, GAS is severely underdocumented, or at least it would be, if it wasn’t for the unofficial docs created by Tranek. While I am glad these docs exist, the fact that documentation of this size and depth was never provided directly by Epic greatly lowers my confidence level with respect to how much Epic plans on supporting developers who use this plugin going forward. Yes, I know that GAS is used in Fortnite, so it will probably never be completely abandoned. However, I think it is safe to say that we are essentially on our own when it comes to figuring out how GAS works.

Epic’s Design Philosophy

With GAS, you are going to end up with a lot of fragmentation with regards to where data and logic for any individual game element is stored. At minimum, you will probably have custom blueprint for your ability, custom blueprints for your ability effects, and gameplay tag definitions to reference these. You may also have custom effect execution logic, gameplay cues, cost effects, and more. All this makes it increasingly difficult to reason about where any particular piece of data lives.

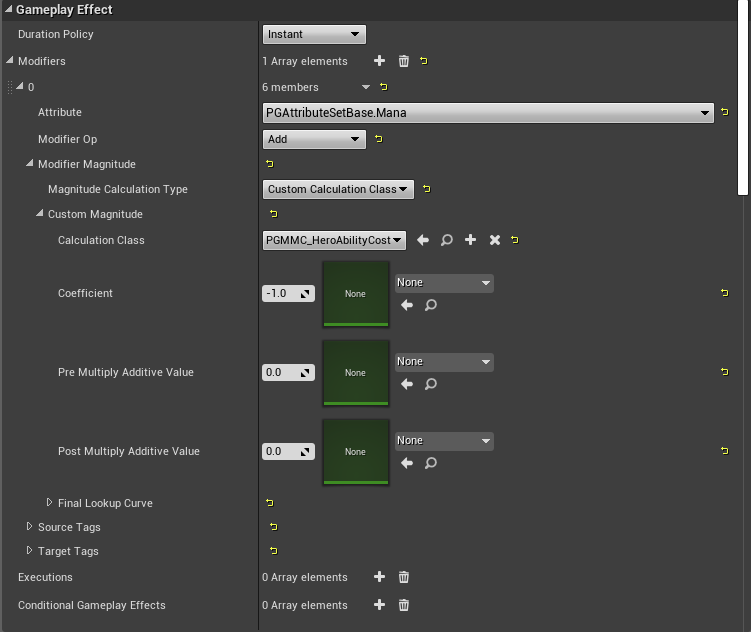

Even when you do know where to look, the organization of the data can get pretty weird. For instance, take a look at this gameplay cost effect example from the Tranek docs. This is an entirely separate gameplay effect you would create just for handling mana consumption. If you implemented this and then an engineer on your project was trying to understand how mana usage works, they would have to look in three separate places:

A relevant GamplayAbility that uses mana, which has cost defined as a scalable float:

UPROPERTY(BlueprintReadOnly, EditAnywhere, Category = "Cost")

FScalableFloat Cost;

The cost MagnitudeCalculation, which defines the logic for computing the cost:

float UPGMMC_HeroAbilityCost::CalculateBaseMagnitude_Implementation(const FGameplayEffectSpec & Spec) const

{

const UPGGameplayAbility* Ability = Cast<UPGGameplayAbility>(Spec.GetContext().GetAbilityInstance_NotReplicated());

if (!Ability)

{

return 0.0f;

}

return Ability->Cost.GetValueAtLevel(Ability->GetAbilityLevel());

}

And the cost GamplayEffect, which actually defines what attribute to use and wires together the magnitude calculation with a -1 coefficient so that it does subtraction instead of addition:

In all likelihood, your player ability will also have this same level of fragmentation for its damage calculation. That’s at minimum another custom data object and logic component for a total of at least five different places you have to look just to understand how a simple spell ability works. Doesn’t this seem a bit much for what should be a fairly simple part of your gameplay architecture? This is by design- Epic’s system architecture is overwhelmingly biased towards extreme fragmentation of data and logic components. Now if you are a studio with 500+ people making the next Fortnite, this might make sense, but the fact is that many of Epic’s systems foist this design philosophy on a lot of developers who simply aren’t going to benefit from structuring their projects in this way.

It feels like whenever Epic’s engineers find themselves considering two design paths- one that would result in a wider feature set but higher complexity, and another that would result in a more barebones system but with lower complexity, they slam the features+complexity button every single time. This leads to a lot of systems that provide the allure of being able to support any imaginable scenario, but with the drawback of forcing you into following closely their design sensibilities.

But What About Multiplayer?

A generally held consensus among most UE devs is that you should not use GAS if you are making a single player game. I agree with this. Without leveraging the networking features of GAS, you simply aren’t getting enough value out of the system to justify the complexity cost. I would argue that even if you are creating a multiplayer game, you should at least approach GAS with a healthy degree of skepticism.

While GAS does provide many nice out-of-the-box networking features, you may still find that it does not support all of your design requirements. For example, GAS cannot predict ability cooldowns. Even more fundamental than ability cooldowns, GAS does not really provide any way to track the state of an ability outside of its lifetime.

My current feeling on GAS for gameplay networking is the following: There is no free lunch. GAS is not going to magically solve all your networking needs. If you choose to use GAS, understand that you will still need to know the network code it provides inside and out in order to build your game. More than likely, you will brush up against some limitation of the system and you will have to either work around it or alter the engine code to get it to work the way that you want. This begs the question: if you need to become an expert on gameplay networking just to use GAS, why not just roll your own network code?

I think for medium to large studios the answer is a no-brainer: hire a network engineer and build something robust from the ground up that will precisely suit your needs. For a small studio, the decision becomes a bit more murky. If you are a small studio that cannot afford to have dedicated network engineers, but you still want to build a multiplayer game, you may be able to squeeze some time savings from having your your engineers learn how to implement GAS instead of building something from scratch. Just keep in mind that you may be forced to cut features if you can’t get GAS to do what you want and don’t have time to implement workarounds.

Conclusion

For single player games, I agree that virtually all developers should stay away. For multiplayer, I think GAS is a great learning resource. As someone who did not know much about gameplay networking prior to using GAS, I learned a lot simply by crawling through the plumbing of the GAS server/client code. However, if you are a solo dev or studio considering using GAS for a multiplayer you should seriously ask yourselves if the complexity cost is really worth maybe having a slightly faster jumpstart on getting your network code up and running.